The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle —alternatively termed the Krebs or citric acid cycle—serves as a central metabolic hub integral to cellular energy generation and precursor biosynthesis. Operating within the mitochondrial matrix of eukaryotes, this pathway is indispensable to aerobic respiration. Its primary role involves oxidizing acetyl-CoA derived from catabolized carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins into carbon dioxide (CO2), while concurrently generating reduced electron carriers (NADH, FADH2). These carriers subsequently fuel oxidative phosphorylation via the electron transport chain (ETC), driving ATP synthesis to meet cellular energy demands.

Beyond energy metabolism, the TCA cycle acts as a biochemical nexus, supplying critical precursors for amino acid, nucleotide, and lipid synthesis. This dual functionality positions it at the intersection of catabolism and anabolism, enabling metabolic flexibility essential for cellular homeostasis. The present review elucidates the cycle's multifunctional roles, its regulatory interplay in cellular metabolism, and its broader implications for maintaining physiological equilibrium.

Energy Production: The Central Role of the TCA Cycle

The TCA cycle is universally recognized for its indispensable contribution to cellular energy generation.

Acetyl-CoA Oxidation

Initiated by acetyl-CoA—a two-carbon metabolite derived from glucose catabolism (via glycolysis), fatty acid β-oxidation, or amino acid deamination—the cycle commences with its condensation into citrate. This reaction merges acetyl-CoA with oxaloacetate (C₄), forming citric acid (C₆) and committing substrates to oxidative metabolism.

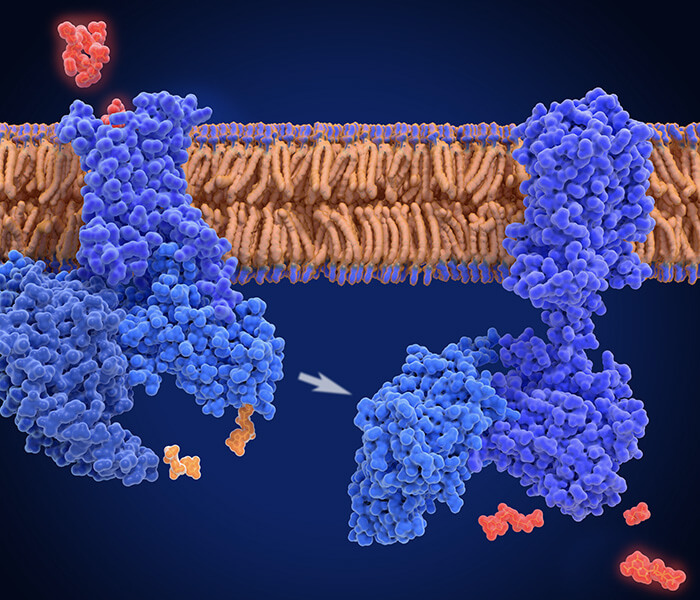

Compartmentalized acetyl-CoA production pathways (Guertin DA et al., 2023).

Compartmentalized acetyl-CoA production pathways (Guertin DA et al., 2023).

Reduced Electron Carrier Synthesis

Throughout the cycle, acetyl-CoA undergoes complete oxidation to CO2, with liberated energy stored as reducing equivalents:

- NADH: Three molecules generated via isocitrate dehydrogenase, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and malate dehydrogenase reactions.

- FADH2: One molecule produced during succinate dehydrogenase-catalyzed oxidation of succinate to fumarate.

Direct ATP Equivalents

The conversion of succinyl-CoA to succinate by succinyl-CoA synthetase facilitates substrate-level phosphorylation, yielding GTP (or ATP in certain tissues) through thioester bond energy utilization.

Oxidative Phosphorylation Coupling

NADH and FADH2 transfer electrons to the mitochondrial ETC, driving proton gradient establishment across the inner membrane. Subsequent ATP synthase activity harnesses this gradient for oxidative phosphorylation. Cumulatively, each TCA cycle iteration supports synthesis of ~10–12 ATP molecules when integrated with ETC activity.

Applications

While glioblastoma (GBM) predominantly relies on glucose metabolism—notably through glycolysis and the Warburg effect—it exhibits metabolic plasticity by utilizing lactic acid as an auxiliary energy substrate. Lactic acid is enzymatically converted to pyruvate, which subsequently enters mitochondria for acetyl-CoA generation. This metabolite serves as a critical substrate for both TCA cycle flux and fatty acid biosynthesis, underpinning cellular survival under nutrient constraints.GBM cells overexpress monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1), facilitating lactic acid uptake to sustain viability during glucose deprivation. This compensatory mechanism rescues cellular energetics by reversing viability loss under hypoglycemic conditions. Furthermore, lactic acid enhances oxidative metabolism by elevating TCA cycle intermediates, thereby promoting mitochondrial ATP production.Intracellular lactic acid metabolism labels acetyl-CoA pools, influencing histone acetylation dynamics. Through ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), lactic acid-derived acetyl-CoA modifies histone marks such as H3K27ac, H3K9ac, and H3K14ac, linking metabolic activity to transcriptional regulation. ACLY inhibition attenuates this acetylation, confirming its role in coupling energy metabolism (oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial function) to epigenetic remodeling.Enrichment analyses associate lactic acid with enhanced mitochondrial oxidative pathways, supporting GBM survival.Seahorse assays demonstrate lactic acid-induced increases in oxygen consumption rate (OCR). Sensitivity to IACS-010759 (complex I inhibitor) highlights oxidative metabolism dependency, while Ndi1 overexpression rescues OCR deficits, underscoring complex I's role in lactic acid utilization.CPI-613, a TCA cycle disruptor, suppresses GBM proliferation and induces apoptosis by blocking critical metabolic intermediates (Torrini C et al., 2022).

Neuronal function in the brain relies heavily on glucose metabolism, where glycolysis generates pyruvate, subsequently converted to acetyl-CoA via the PDHC. As a primary substrate for theTCA cycle, acetyl-CoA drives mitochondrial energy production essential for neurotransmitter synthesis and neuronal activity. In neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), PDHC dysfunction reduces acetyl-CoA availability, impairing mitochondrial energetics and compromising acetylation-dependent processes. This metabolic disruption leads to regional energy deficits and suppressed post-translational modifications critical for neuronal homeostasis.Acetyl-CoA serves as a pivotal precursor for acetylcholine (ACh) biosynthesis, mediated by choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) in cholinergic neurons. Reduced ChAT activity, often linked to acetyl-CoA depletion in AD, directly diminishes ACh production, exacerbating cognitive and motor deficits. Mitochondrial synthesis deficits and cytoplasmic utilization inefficiencies underlie acetyl-CoA scarcity in AD brains, further aggravated by neurotoxic insults (e.g., metal ion dysregulation or toxin exposure), which inhibit both acetyl-CoA and ACh generation.Altered acetyl-CoA levels modulate enzymatic activity across pathways involving carnitine acetyltransferase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase, influencing metabolic plasticity under physiological and pathological states. Cellular zinc excess, as observed in excitotoxicity, disrupts energy equilibrium, impairing postsynaptic function and promoting amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation. Such metabolic imbalances exacerbate neuronal signaling defects and accelerate neurodegenerative progression.Acetyl-CoA distribution varies across neural cells, reflecting functional specialization. Cholinergic neurons, despite their high acetyl-CoA demand, exhibit lower baseline levels, rendering them vulnerable to metabolic stress. PDHC, critical for sustaining acetyl-CoA pools, is inhibited by AD-associated pathologies (Aβ, Tau), amplifying energy deficits. Neuroimaging studies correlate reduced cerebral glucose uptake (F18-deoxyglucose PET) and cholinergic ligand binding in AD patients with acetyl-CoA depletion, underscoring its clinical relevance. Notably, while Aβ deposition is a hallmark, its symptomatic linkage is inconsistent, implicating PDHC-driven energy failure as a central pathogenic driver (Ronowska A et al., 2018).

While malignant tumors exhibit elevated glycolytic activity (Warburg effect), mitochondrial metabolism remains indispensable for oncogenesis. Mitochondria sustain cellular bioenergetics through oxidative phosphorylation and generate reducing equivalents (NADH, FADH₂) via the TCA)cycle, which drive electron transport chain (ETC) activity to maximize ATP yield. Beyond energy production, mitochondrial pathways metabolize diverse substrates—glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids—to meet biosynthetic demands. The TCA cycle serves as a carbon hub, assimilating glucose-derived pyruvate, glutamine, fatty acids, and lactate to fuel anabolic processes critical for cancer proliferation.Therapeutic strategies exploiting mitochondrial dependencies include:Suppressing ETC complex I (NADH dehydrogenase), pyruvate dehydrogenase, or TCA enzymes to disrupt energy metabolism.Inducing proteolytic degradation of respiratory enzymes via CLPP upregulation, impairing oxidative phosphorylation.Promoting apoptosis through BCL-2 pathway modulation (e.g., ABT-263).Gamitrinib-mediated disruption of mitochondrial chaperone TRAP1 to compromise stress adaptation. FOXO3-dependent induction of TRAIL expression enhances apoptosis when combined with BH3 mimetics.CLPP-Mediated Enzyme Depletion: Respiratory enzyme degradation exacerbates metabolic stress in cancer cells (Shang E et al., 2023).

Aconitase 2 (ACO2), a central enzyme in the TCA cycle, catalyzes the isomerization of citrate to isocitrate, a reaction critical for generating NADH and FADH₂. These electron carriers fuel oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to synthesize ATP, thereby sustaining cellular energy homeostasis. Emerging evidence positions ACO2 as a regulator of lipid biosynthesis, with experimental studies in 3T3-L1 adipocytes demonstrating that ACO2 overexpression enhances lipid accumulation, mitochondrial biogenesis, and ATP production. Conversely, ACO2 deficiency suppresses adipogenic processes, reduces mitochondrial mass, and diminishes ATP levels. Notably, isocitrate supplementation rescues these deficits, confirming substrate dependency in ACO2-mediated metabolic regulation.Mechanistically, the pro-lipogenic effects of ACO2 rely on ATP availability, as demonstrated by rotenone-induced respiratory chain inhibition, which abolishes ACO2-driven lipid biosynthesis. These findings establish a functional link between TCA cycle activity (via ACO2) and lipid metabolism, wherein mitochondrial ATP output directly modulates adipogenic capacity (Chen Y et al., 2020).

Biosynthetic Precursor Supply

Beyond its primary role in energy generation, the TCA cycle serves as a critical reservoir of intermediates for essential biomolecule production. This dual functionality positions the TCA cycle as a central hub of cellular metabolism.

Amino Acid Biosynthesis

- α-Ketoglutarate: Acts as a precursor molecule for glutamate, glutamine, proline, and arginine.

- Oxaloacetate: Provides the backbone for aspartate, asparagine, methionine, threonine, and lysine synthesis.

- Succinyl-CoA: Essential for porphyrin (e.g., heme) and methionine production.

Nucleotide Production

- Oxaloacetate: Converted to aspartate, a precursor for pyrimidine bases (cytosine, thymine, uracil).

- α-Ketoglutarate: Contributes to purine biosynthesis, including adenine and guanine.

Lipid and Cholesterol Formation

- Citrate: Exported to the cytosol and cleaved into acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate. Acetyl-CoA fuels fatty acid elongation and cholesterol synthesis.

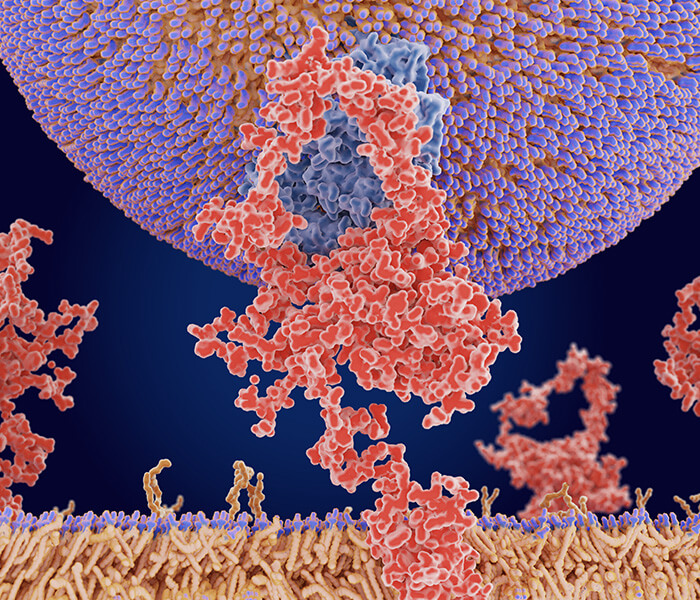

Carbon connectivity reveals reverse (reductive) TCA flux in hypoxia: fatty acid synthesis is routed though IDH1 and IDH2 (Filipp FV et al., 2012).

Carbon connectivity reveals reverse (reductive) TCA flux in hypoxia: fatty acid synthesis is routed though IDH1 and IDH2 (Filipp FV et al., 2012).

Heme Assembly

- Succinyl-CoA: A central intermediate in heme biosynthesis, critical for hemoglobin and cytochrome prosthetic groups.

Applications

African swine fever virus (ASFV) infection induces marked metabolic alterations, notably affecting amino acid homeostasis and TCA cycle intermediates. During early infection, amino acid levels surge, followed by a decline in later stages. Concurrently, ASFV enhances TCA cycle activity, elevating citrate, succinate, α-ketoglutarate, and oxaloacetate concentrations. This metabolic shift drives increased aspartate and glutamate synthesis, facilitating viral replication.ASFV elevates lactate levels through lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, suppressing innate immunity by inhibiting RIG-I-mediated interferon-β (IFN-β) production. Pharmacological modulation confirms this mechanism:UK-5099 (pyruvate carrier inhibitor): Amplifies lactate, exacerbating IFN-β suppression and enhancing viral replication.GSK2837808A (LDH inhibitor): Reduces lactate, restoring IFN-β expression and curtailing ASFV proliferation.In porcine alveolar macrophages (PAMs), ASFV replication (confirmed by viral titers and P30 protein expression) correlates with progressive apoptosis, peaking at 48 hours post-infection. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QTOF-MS) revealed metabolic perturbations, including upregulated amino acids, glycolytic intermediates, and TCA cycle metabolites. KEGG pathway analysis highlighted disruptions in alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism.Aspartate and TCA Activation: Elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activity in PAMs and serum underscores the interplay between aspartate metabolism and TCA cycle flux. Exogenous aspartate or T23 (TCA enhancer) significantly boosts ASFV replication.Glutamate and α-Ketoglutarate: Their pro-viral effects are concentration-dependent, with higher levels accelerating replication (Xue Q et al., 2022).

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the most prevalent chronic hepatic disorder globally, is characterized by abnormal lipid deposition and is strongly associated with metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular complications. Acetyl-CoA, a central metabolic hub, regulates lipid homeostasis through its involvement in cholesterol biosynthesis, fatty acid oxidation, and amino acid metabolism.Iron imbalance exerts dual effects on NAFLD progression:Iron Overload: Dietary iron excess disrupts hepatic fatty acid metabolism, potentially exacerbating NAFLD by altering acetyl-CoA flux. Paradoxically, in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice, iron supplementation (HFD+Fe) reduced hepatic lipid accumulation and NAFLD severity scores compared to HFD alone.Iron Deficiency: Conversely, low iron levels correlate with obesity and steatosis, underscoring the importance of iron equilibrium in lipid regulation.In HFD+Fe mice, hepatic acetyl-CoA levels were markedly suppressed, accompanied by:Downregulation of acetyl-CoA metabolic enzymes linked to cholesterol synthesis, glycolysis, and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, including PDHB (glycolysis) and IDH3A (TCA cycle).Reduced mitochondrial membrane potential and antioxidant depletion, indicative of oxidative stress.Decreased serum and hepatic cholesterol, LDL-C, and ATP levels, suggesting compromised energy production.Despite attenuated steatosis, HFD+Fe mice exhibited hepatotoxicity, evidenced by elevated AST/ALT levels and increased TUNEL-positive cells. This dichotomy implies that iron overload mitigates NAFLD progression by limiting acetyl-CoA availability for cholesterol synthesis, yet concurrently induces mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage (Luo G et al., 2022).

Adipocytes utilize diverse carbon substrates to synthesize Acetyl-CoA, a central metabolite fueling both the TCA cycle and de novo lipid biosynthesis. Glucose uptake via insulin-responsive GLUT4 transporters enables mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, while circulating free fatty acids (FFAs) and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) serve as alternative acetyl-CoA precursors. Within adipocytes, acetyl-CoA and NADPH act as essential cofactors for lipogenesis, with their production tightly regulated by enzymatic activity. For instance, ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) and malic enzyme 1 (ME1) catalyze critical steps in converting citrate—a TCA cycle intermediate—into acetyl-CoA, thereby supplying substrates for fatty acid elongation.ACLY, a rate-limiting enzyme in adipocyte lipogenesis, demonstrates dietary plasticity: its expression is upregulated by carbohydrate intake but suppressed under high-fat conditions. Genetic ablation of ACLY in murine models induces mild lipodystrophy and reduces circulating lipids, suggesting therapeutic potential for metabolic disorders. Notably, sex-specific differences emerge in lipid storage dynamics. Female adipocytes exhibit heightened lipogenic capacity compared to males, rendering them more susceptible to metabolic dysfunction (e.g., insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis) upon ACLY deficiency.ACSS2 compensates for acetyl-CoA deficits by converting acetate into acetyl-CoA, sustaining lipid synthesis even when canonical pathways are impaired. Beyond its role in lipogenesis, acetyl-CoA modulates histone acetylation, linking nutrient availability to chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes. This metabolic-epigenetic interplay is further influenced by β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), a ketone body generated during fatty acid oxidation. BHB inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs), enhancing acetylation-mediated gene activation and potentially rejuvenating aging adipocytes' differentiation capacity (Felix JB et al., 2021).

Lysine succinylation, a critical post-translational modification, governs diverse cellular processes. During erythropoiesis, elevated succinyl-CoA levels correlate with heightened lysine succinylation. Experimental suppression of this modification—via succinyltransferase knockdown or SIRT5 desuccinylase overexpression—disrupts erythroid progenitor proliferation, elevates apoptosis, and impedes terminal differentiation, underscoring its necessity in red blood cell development.Global profiling identified 939 succinylated proteins harboring 3,562 modification sites, distributed across cellular compartments and linked to multifunctional pathways. Notably, succinylation can modulate protein activity independently of expression-level alterations. A prominent example involves KAT2A-mediated succinylation at histone H3K79, which drives chromatin remodeling to orchestrate erythroid maturation.Erythropoietic function of CYCS depends on succinylation at residues K28/K40, positioning it as a regulatory nexus.Succinyl-CoA abundance peaks during early and late erythroid differentiation, with succinylation surpassing acetylation and methylation in prevalence, highlighting its stage-specific dominance.Western blot analyses of differentiating human CD34+ cells revealed progressive succinylation accrual, particularly in nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. Proteins with multiple succinylation sites (e.g., SLC4A1, SPTA1, SPTB) exhibited pronounced modification during late differentiation. Dynamic succinylation patterns aligned with critical processes, including metabolic adaptation and chromatin restructuring. KAT2A-catalyzed H3K79 succinylation emerged as a transcriptional rheostat, facilitating gene activation essential for erythroid commitment (Hu B et al., 2025).

Services You May Be Interested In:

Additional Resources:

Redox Homeostasis and Metabolic Integration via the TCA Cycle

The TCA cycle sustains cellular redox equilibrium by modulating NAD⁺/NADH and FAD/FADH₂ ratios, ensuring efficient energy metabolism and oxidative stress mitigation.

NAD⁺ Recycling

Key TCA intermediates—isocitrate, α-ketoglutarate, and malate—undergo oxidation to produce NADH. Subsequent electron transport chain (ETC) activity regenerates NAD⁺, which is indispensable for sustaining glycolysis and iterative TCA flux.

FAD Replenishment

Succinate oxidation to fumarate generates FADH₂, which is reoxidized to FAD via the ETC, maintaining FAD-dependent enzymatic activity.

Oxidative Stress Modulation

By sustaining efficient ETC electron flux, the TCA cycle limits ROS overproduction. Cycle dysfunction disrupts this balance, inducing oxidative damage and compromising cellular integrity.

Applications

ROS, generated through aerobic metabolism, antimicrobial treatments, and host immune activation, compromise cellular integrity by damaging biomolecules, thereby reducing bacterial viability and inducing cell death. Enzymes harboring iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters, such as those in the TCA cycle, are especially susceptible to ROS-mediated oxidation, resulting in functional impairment.Five Fe-S-containing TCA cycle enzymes are primary targets of oxidative stress. Studies using Salmonella enterica (STM) mutants lacking cytoplasmic superoxide dismutase (ΔsodAB)—which accumulate superoxide anions (SOA)—revealed decreased aconitase (AcnA/B) levels, mirroring metabolic profiles of ΔacnAB strains. Proteomic analyses indicated reduced acnA expression in ΔsodAB mutants, alongside heightened stress responses despite unchanged survival in macrophages or under methyl viologen exposure. These findings suggest ROS-induced aconitase suppression does not directly attenuate bacterial virulence but amplifies intracellular ROS, potentially enhancing antibiotic efficacy and host immune clearance.The TCA cycle both contributes to and is vulnerable to ROS. Fe-S cluster damage in enzymes like aconitase and fumarase disrupts metabolic flux, as observed in E. coli mutants deficient in antioxidant defenses. Such strains exhibit diminished TCA enzyme levels (e.g., AcnA/B, FumA/B) and accumulate intermediates (citrate, cis-aconitate). In STM ΔacnAB, glycolytic intermediates decline while TCA metabolites surge, contrasting with minimal changes in fumarase-deficient (ΔfumABC) strains. Chronic ROS exposure reduces AcnA expression and stability, impairing cycle functionality.ROS-altered TCA activity extends to amino acid biosynthesis, with perturbations in arginine, proline, and lysine levels linking oxidative stress to biosynthetic pathway dysregulation. This dual disruption of energy metabolism and anabolic processes underscores ROS's systemic impact on bacterial physiology (Noster J et al., 2019).

Tryptophan predominantly undergoes catabolism via the kynurenine pathway, yielding metabolites with significant biological roles. In oncological contexts, kynurenine exerts immunosuppressive effects by impairing T-cell activity, thereby fostering tumor immune evasion and progression. Metabolites such as kynurenic acid, quinolinic acid, and 3-hydroxykynurenine (3HK) exhibit dual roles in neurodegenerative disorders: quinolinic acid induces neuronal apoptosis through NMDA receptor overactivation, whereas kynurenic acid offers neuroprotection. 3HK demonstrates concentration-dependent effects, acting as an antioxidant at low levels but promoting oxidative stress and neuronal death at elevated concentrations, particularly under pro-oxidant conditions.In human colon carcinoma cells (HCT116), 3HK disrupts TCA cycle dynamics, marked by elevated citrate and aconitate levels alongside diminished isocitrate and downstream intermediates, indicative of aconitase inhibition. This perturbation correlates with ROS accumulation, as evidenced by depleted reduced GSH and compromised antioxidant defenses. Dose-dependent reductions in cell viability after 48-hour 3HK exposure suggest ROS-mediated apoptosis. Genetic silencing of KYNU, a pivotal enzyme in tryptophan metabolism, exacerbates oxidative stress, diminishes cell survival, and triggers apoptosis, as confirmed by annexin V assays. These findings posit KYNU as a critical regulator of 3HK levels, with implications for xanthohumolic acid synthesis and free radical-mediated cytotoxicity.Notably, many malignancies overexpress indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), a key enzyme in tryptophan catabolism, highlighting metabolic vulnerabilities exploitable for therapeutic intervention. Targeting KYNU emerges as a promising strategy to amplify oxidative stress in cancer cells by disrupting tryptophan metabolic flux, thereby inducing selective cytotoxicity. This approach underscores the interplay between metabolic reprogramming and oxidative balance in oncotherapy (Buchanan JL et al., 2023).

Metabolic Crossroads

The TCA cycle integrates carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid catabolism, serving as a central hub for substrate interconversion.

Carbohydrate Catabolism

Glycolysis catabolizes glucose to pyruvate, which is decarboxylated to acetyl-CoA via the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) for TCA entry.

Lipid Utilization

β-Oxidation of fatty acids yields acetyl-CoA, fueling the TCA cycle to meet energy demands.

Amino Acid Integration

Deamination of amino acids generates TCA intermediates (e.g., glutamate→α-ketoglutarate, aspartate→oxaloacetate), coupling protein breakdown to ATP synthesis.

Applications

SLC13A2, a citrate transporter critical for hepatic metabolic recovery, facilitates citrate uptake into hepatocytes, thereby enhancing acetyl-CoA synthesis via ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY). This process underpins de novo cholesterol biosynthesis, essential for hepatocyte proliferation and liver regeneration.SLC13A2 is transiently downregulated post-liver injury but recovers alongside functional restoration, correlating with regenerative capacity.CRISPR/Cas9-mediated SLC13A2 deletion in mice showed no baseline metabolic alterations (e.g., glucose, weight, or lipid pathways) but severely impaired liver regeneration post-partial hepatectomy (PHx), evidenced by reduced liver-to-body weight ratios and diminished Ki67+ proliferating cells.SLC13A2 upregulation accelerated hepatic recovery post-PHx, marked by hypoglycemia, increased polyploid hepatocytes, and elevated cholesterol synthesis genes (SREBP2, LDLR, HMGCR).SLC13A2-driven citrate influx boosts ACLY activity, elevating acetyl-CoA pools for cholesterol production. Inhibitors targeting HMGCR or ACLY abrogate SLC13A2-mediated regeneration, confirming pathway specificity.Overexpression amplifies cholesterol metabolites (e.g., zymostenol), it minimally affects triglycerides or fatty acid metabolism, highlighting its focused role in sterol regulation.SLC13A2 uniquely coordinates TCA intermediate transport during regeneration, distinct from other solute carriers. Post-PHx, its expression dynamically aligns with hepatic mass restoration, underscoring its role in balancing anabolic-catabolic demands(Shi L et al., 2025).

Clinical and Pathological Relevance of the TCA Cycle

While indispensable for cellular homeostasis, dysregulation of the TCA cycle contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple diseases, reflecting its dual role in health and pathology.

Oncological Implications

Malignant cells frequently exhibit metabolic reprogramming, prioritizing aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) over oxidative phosphorylation despite oxygen availability. This shift is accompanied by dysregulated TCA cycle flux, which supports biomass synthesis and redox balance for tumor proliferation.

Neurodegenerative Pathologies

Neuronal TCA cycle impairment disrupts mitochondrial energetics, exacerbating oxidative stress and ATP deficits. Such metabolic dysfunction is implicated in neurodegenerative cascades, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, where mitochondrial failure accelerates protein aggregation and synaptic loss.

Metabolic Syndrome

Aberrant TCA cycle activity correlates with systemic metabolic disturbances, including insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Disrupted cycle intermediates impair glucose homeostasis and lipid handling, perpetuating a vicious cycle of metabolic dysregulation.

Applications

While the canonical TCA cycle is critical for cellular energy production, bacterial systems often employ metabolic adaptations under environmental stressors. Under aluminum (Al) toxicity, for instance, certain bacteria activate a modified TCA pathway to enhance survival. This alternative route prioritizes oxalate synthesis—a dicarboxylic acid that chelates Al³⁺ ions, mitigating their toxicity—while generating ATP via substrate-level phosphorylation rather than oxidative phosphorylation.Metabolic Reprogramming Under Aluminum Stress:Isocitrate lyase (ICL) and acylated glyoxylate dehydrogenase (AGODH) are markedly upregulated, driving glyoxylate and oxalate production. AGODH's prominence in Al-stressed cells underscores its role in detoxification.Elevated activity of succinyl-CoA synthetase (SCS) and oxalate-CoA transferase (OCT) enables ATP generation from oxalyl-CoA, bypassing traditional TCA steps. This pathway sustains energy balance despite reduced NADH/CO₂ output.Citrate, succinate, and glyoxylate levels shift significantly, with glyoxylate accumulation linked to oxalate production. Despite stable ATP levels, oxidative phosphorylation declines, evidenced by reduced activity of complexes I and IV, as well as enzymes like aconitase (ACN) and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH).Al exposure disrupts heme biosynthesis, suggesting cross-talk between Al toxicity and iron homeostasis. Impaired heme synthesis likely stems from Al interference with iron uptake or utilization, further complicating metabolic adaptation (Singh R et al., 2009).

Glioblastoma (GBM) cells sustain their rapid proliferation through dual ATP production via glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). To disrupt these energy pathways, a therapeutic strategy combining the small-molecule inhibitor EPIC-0412 with metabolism-targeting agents—arachidonic acid trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3) and 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG)—was evaluated in murine models and patient-derived GBM cells. This triple-target approach significantly suppressed tumor growth and extended survival by concurrently inhibiting the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, phospholipid metabolism, and glycolytic flux.EPIC-0412 disrupts the long noncoding RNA HOTAIR-EZH2 interaction, impairing tumor metabolism. Treatment with EPIC-0412 reduced TCA cycle intermediates (citrate, cis-aconitate, isocitrate, α-ketoglutarate, fumarate) and depleted ATP levels by ~70%, indicating mitochondrial dysfunction. AACOCF3 exacerbated ATP suppression by altering phospholipid metabolism, which impedes glioma cell endocytosis and proliferation.EPIC-0412 elevated ATF3 expression via H3K27 methylation modulation, which bound the SDHA promoter (confirmed by ChIP assay) to repress its transcription. SDHA downregulation disrupted TCA cycle integrity, correlating with reduced oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and proliferative arrest. Flow cytometry revealed G0/G1 phase accumulation post-treatment, driven by p21-mediated inhibition of cyclin D1, CDK4, and CDK6. Exogenous ATP partially reversed cell cycle arrest, confirming ATP's pivotal role in proliferation.Although RTK-RAS-PI3K pathway activation (e.g., via KRAS/EGFR-vIII mutants) enhanced ATP synthesis in GBM, the EPIC-0412/AACOCF3 combination effectively counteracted this adaptation. This synergy underscores the potential of dual metabolic targeting to overcome compensatory signaling in aggressive malignancies (Yang S et al., 2022).

The TCA cycle serves as a central metabolic hub, coupling catabolic processes (e.g., glucose/fatty acid oxidation) with anabolic precursor synthesis (amino acids, nucleotides). Beyond energy generation, it maintains cellular metabolic equilibrium, making its enzymes critical targets in pathological states.α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (OGDHc), a rate-limiting TCA enzyme, catalyzes the conversion of α-ketoglutarate (αKG) to succinyl-CoA while generating NADH and ATP via oxidative phosphorylation. This reaction is indispensable for cellular bioenergetics, macromolecule biosynthesis, and redox balance. In malignancies, OGDHc activity modulation critically supports proliferative demands by governing metabolic flux. Dysregulated OGDHc drives metabolite accumulation (e.g., fumarate), stabilizes HIF-1α, and elevates ROS, fostering tumor progression.As a flavin-dependent enzyme, OGDHc is prone to electron transfer inefficiency, contributing to mitochondrial ROS generation. Its sensitivity to lipid peroxidation byproducts (e.g., 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, HNE) links it to antioxidant response activation. This dual role positions OGDHc as a redox sensor, with dysfunction disrupting metabolite flow and exacerbating oncogenic metabolism. Targeting OGDHc—via inhibitors like succinyl phosphonate—alters cancer cell viability, migration, and chemoresistance, highlighting its therapeutic promise. Circ-OGDH: This circular RNA, derived from the OGDH locus, acts as an oncogenic driver in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. It enhances glutamine catabolism, αKG production, and ATP synthesis while suppressing miR-615-5p to upregulate PDX1 and TPX2, fueling proliferation and invasion.A brain/liver-enriched OGDH paralog, functions as a tumor suppressor. Its downregulation in colorectal, hepatic, and pancreatic cancers disrupts TCA cycle integrity, impairing antioxidant capacity and lipid homeostasis. OGDHL loss activates αKG-dependent mTOR signaling, promoting lipogenesis and chemoresistance. Conversely, OGDHL overexpression induces ROS-mediated apoptosis and ameliorates neurodegenerative pathology in Alzheimer's models by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling.The dichotomous roles of OGDH-related molecules underscore their context-dependent therapeutic relevance. While OGDHc inhibition may curb cancer progression, OGDHL restoration could counteract metabolic reprogramming in tumors or mitigate neurodegeneration (Chang LC et al., 2022).

References

- Torrini C, Nguyen TTT, Shu C, Mela A, Humala N, Mahajan A, Seeley EH, Zhang G, Westhoff MA, Karpel-Massler G, Bruce JN, Canoll P, Siegelin MD. "Lactate is an epigenetic metabolite that drives survival in model systems of glioblastoma." Mol Cell. 2022 Aug 18;82(16):3061-3076.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.06.030

- Ronowska A, Szutowicz A, Bielarczyk H, Gul-Hinc S, Klimaszewska-Łata J, Dyś A, Zyśk M, Jankowska-Kulawy A. "The Regulatory Effects of Acetyl-CoA Distribution in the Healthy and Diseased Brain." Front Cell Neurosci. 2018 Jul 10;12:169. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00169

- Shang E, Nguyen TTT, Westhoff MA, Karpel-Massler G, Siegelin MD. "Targeting cellular respiration as a therapeutic strategy in glioblastoma." Oncotarget. 2023 May 4;14:419-425. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.28424

- Chen Y, Cai GH, Xia B, Wang X, Zhang CC, Xie BC, Shi XC, Liu H, Lu JF, Zhang RX, Zhu MQ, Liu M, Yang SZ, Yang Zhang D, Chu XY, Khan R, Wang YL, Wu JW. "Mitochondrial aconitase controls adipogenesis through mediation of cellular ATP production." FASEB J. 2020 May;34(5):6688-6702. doi: 10.1096/fj.201903224RR

- Xue Q, Liu H, Zhu Z, Yang F, Song Y, Li Z, Xue Z, Cao W, Liu X, Zheng H. "African Swine Fever Virus Regulates Host Energy and Amino Acid Metabolism To Promote Viral Replication." J Virol. 2022 Feb 23;96(4):e0191921. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01919-21

- Luo G, Xiang L, Xiao L. "Acetyl-CoA Deficiency Is Involved in the Regulation of Iron Overload on Lipid Metabolism in Apolipoprotein E Knockout Mice." Molecules. 2022 Aug 4;27(15):4966. doi: 10.3390/molecules27154966

- Felix JB, Cox AR, Hartig SM. "Acetyl-CoA and Metabolite Fluxes Regulate White Adipose Tissue Expansion." Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021 May;32(5):320-332. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2021.02.008

- Hu B, Gong H, Nie L, Zhang J, Li Y, Liu D, Zhang H, Zhang H, Han L, Yang C, Li M, Xu W, Nakamura Y, Shi L, Ye M, Hillyer CD, Mohandas N, Liang L, Sheng Y, Liu J. "Lysine succinylation precisely controls normal erythropoiesis." Haematologica. 2025 Feb 1;110(2):397-413. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2024.285752

- Noster J, Persicke M, Chao TC, Krone L, Heppner B, Hensel M, Hansmeier N. "Impact of ROS-Induced Damage of TCA Cycle Enzymes on Metabolism and Virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium." Front Microbiol. 2019 Apr 24;10:762. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00762

- Buchanan JL, Rauckhorst AJ, Taylor EB. "3-hydroxykynurenine is a ROS-inducing cytotoxic tryptophan metabolite that disrupts the TCA cycle." bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Jul 10:2023.07.10.548411. doi: 10.1101/2023.07.10.548411

- Shi L, Chen H, Zhang Y, An D, Qin M, Yu W, Wen B, He D, Hao H, Xiong J. "SLC13A2 promotes hepatocyte metabolic remodeling and liver regeneration by enhancing de novo cholesterol biosynthesis." EMBO J. 2025 Mar;44(5):1442-1463. doi: 10.1038/s44318-025-00362-y

- Singh R, Lemire J, Mailloux RJ, Chénier D, Hamel R, Appanna VD. "An ATP and oxalate generating variant tricarboxylic acid cycle counters aluminum toxicity in Pseudomonas fluorescens." PLoS One. 2009 Oct 7;4(10):e7344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007344

- Yang S, Zhao J, Cui X, Zhan Q, Yi K, Wang Q, Xiao M, Tan Y, Hong B, Fang C, Kang C. "TCA-phospholipid-glycolysis targeted triple therapy effectively suppresses ATP production and tumor growth in glioblastoma." Theranostics. 2022 Oct 3;12(16):7032-7050. doi: 10.7150/thno.74197

- Chang LC, Chiang SK, Chen SE, Hung MC. "Targeting 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase for cancer treatment." Am J Cancer Res. 2022 Apr 15;12(4):1436-1455.Targeting 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase for cancer treatment - PubMed