Protein aggregation presents a significant challenge in the biopharmaceutical industry, affecting drug development by potentially reducing therapeutic efficacy and introducing immunogenicity risks that may compromise patient safety. The formation of aggregates, whether in antibodies, enzymes, or other therapeutic proteins, is often closely related to manufacturing processes, storage conditions, and molecular characteristics. This paper delves into the mechanisms underlying protein aggregation and systematically analyzes the factors influencing it. By exploring critical control points within cell culture conditions and production processes, we aim to provide scientific insights for optimizing drug quality.

Impact of Protein Aggregation on Drug Safety and Efficacy

Impact on Safety:

The relationship between protein aggregation, anti-drug antibodies (ADAs), and immunogenicity has been extensively explored across various studies. While the impact of aggregation on ADAs, as well as the relationship between ADAs and clinical immunogenicity, are frequently studied independently, the role of protein aggregation in enhancing immunogenicity is unequivocal. Researchers have induced subvisible aggregation in antibodies via multiple methods to investigate its effects on stimulating dendritic cells (DCs) in vitro. Findings indicate that subvisible aggregates can upregulate costimulatory molecules on dendritic cells in vitro, subsequently provoking a humoral immune response.

Manifestations of adverse effects due to ADA reactions have been reported in approved therapeutics. For instance, among numerous rheumatoid arthritis patients, the emergence of ADAs against adalimumab is closely linked to reduced serum drug levels and loss of therapeutic response.

Protein aggregates pose a risk concerning immunogenic responses in therapeutic protein products, especially those associated with clinical adverse reactions. Noteworthy are the neutralizing antibodies that inhibit product efficacy, and more critically, cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies that target endogenous protein byproducts. Severe immediate hypersensitivity reactions, such as allergic responses, further illustrate the significant impact of protein aggregation on drug safety.

Impact on Efficacy:

Protein aggregates can directly activate B cells via T-cell-independent pathways, leading to the production of short-lived plasma cells, ultimately resulting in the generation of ADAs. These antibodies primarily include IgG2b, IgG3, or IgM isotypes. ADAs can be classified into non-neutralizing and neutralizing subtypes. Non-neutralizing ADAs bind to epitopes that do not interfere with the interaction between the protein drug and its target, minimally affecting drug activity. In contrast, neutralizing ADAs can obstruct the drug's active sites, significantly diminishing its efficacy.

The formation of soluble or insoluble aggregates (particles) in protein drug products is a substantial challenge as these aggregates can markedly reduce biological activity. For example, literature reports indicate that the antiviral activity of IFN-γ in its polymeric form is four to eight times lower than that in its oligomeric form. Moreover, the immune response-generated ADAs may variably influence therapeutic efficacy and alter the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of biotherapeutics. These observations underscore the adverse effects of protein aggregation on drug efficacy.

Mechanisms of Protein Aggregate Formation

Initial Oligomerization/Nucleation

The initial oligomerization or nucleation of proteins represents the incipient phase in the formation of protein aggregates. Proteins may inherently possess conformational distortions or localized instabilities, which unveil aggregation-prone sequences, referred to as "hotspot sequences." These sequences facilitate the formation of aggregation-prone monomers that subsequently associate to form dimers or oligomers. This primary aggregation event is conventionally termed nucleation.

Literature evidence suggests that "hotspot sequences" can be situated in various regions of the protein. For instance, in monoclonal antibodies, the Fab domain may harbor such sequences. A folded monoclonal antibody comprises defined structural domains, and conformational distortion or "misfolding" within the Fab domain can expose aggregation-prone amino acid extensions. This exposure subsequently induces the aggregation of protein monomers into soluble oligomers or polymers.

The aggregation process involves several protein-protein interactions, such as hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, which are concentration-dependent; an increase in protein concentration promotes the proximity and association of monomers into oligomers or polymers. Additionally, inappropriate solvent conditions, including low pH, destabilizing agents, organic solvents, or pressure, may induce local conformational instability. The initial nucleation rate of protein aggregates is closely linked to conformational stability and flexibility. Collectively, these factors synergistically drive the initial oligomerization/nucleation of proteins.

Aggregate Growth

Following oligomer formation, the process advances to the aggregate growth phase, wherein oligomers progressively develop into larger polymers. This growth is facilitated through multiple mechanisms, including monomer addition—where individual monomers continuously join pre-formed oligomers, thus expanding their scale; chain-like aggregation—akin to chain extension; inter-aggregate or inter-cluster interactions—where distinct aggregates coalesce; and coagulation.

The growth of aggregates is intricately tied to the conformational stability of the protein and its colloidal stability. Similar to nucleation, proteins with unstable conformations are more prone to further aggregation reactions that facilitate aggregate growth. Moreover, colloidal stability significantly affects aggregate growth; diminished colloidal stability enhances inter-aggregate interactions, thereby accelerating aggregate formation. Over time, the number of nucleation sites and initial aggregates increases, leading to an exponential growth of aggregates. Eventually, protein aggregates expand into insoluble particles, the morphological diversity of which correlates with the relative abundance of hydrophobic or aromatic amino acids and the particular aggregation stage. Furthermore, studies have indicated that insoluble protein particles may partially dissociate into soluble polymers after a certain period.

Factors Influencing Protein Aggregation

1. Primary Structure of Proteins

The primary structure of proteins, specifically the sequence of amino acids, plays a crucial role in protein aggregation. The relative abundance and arrangement of hydrophobic amino acids have a significant impact, as these amino acids tend to form aggregation-prone regions, thereby fostering the occurrence of protein aggregates. The propensity for aggregation is influenced not only by aggregation-prone sequences but also by the amphiphilic proportion of the sequence oligomers. Introducing one or more distinct hydrophobic amino acids at specific positions can markedly accelerate the aggregation rate.

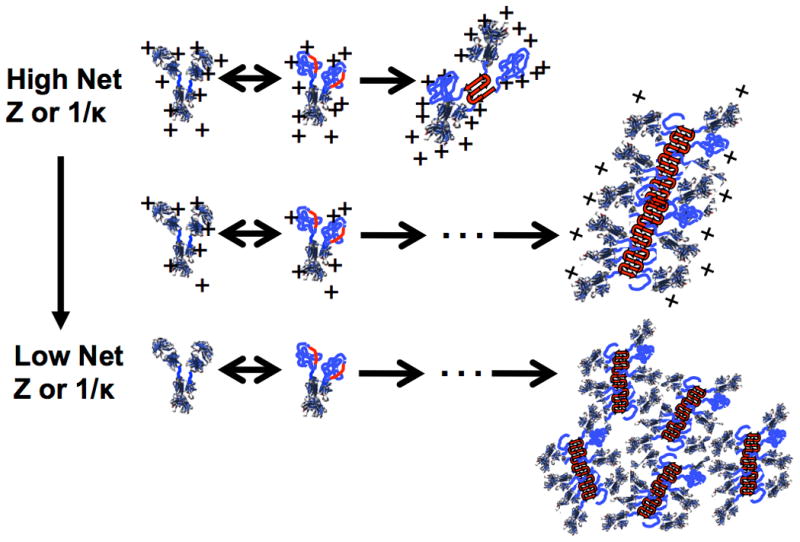

Aggregation propensity based on net charge and screening length.

Aggregation propensity based on net charge and screening length.Glycosylation is also a pivotal factor in influencing protein aggregation. For many proteins, glycosylation is critical for stability. Taking antibodies as an example, glycosylation of the CH2 domain stabilizes both the domain and the entire antibody molecule. Conversely, deglycosylation may disrupt the tertiary structure of the CH2 domain, resulting in instability in the Fc region, thereby accelerating aggregation. The type of glycan structures within a protein can also alter its tendency to aggregate by affecting conformational stability. Different glycan structures impart distinct physicochemical properties to proteins, impacting inter-molecular interactions, ultimately influencing protein aggregation. Therefore, elements such as amino acid sequences, hydrophobic residues, and glycosylation within the primary structure of proteins are significant contributors to protein aggregation.

2. Chemical Degradation or Modification

Throughout the lifecycle of protein-based pharmaceuticals—from development and production to storage—proteins undergo various chemical degradation pathways that significantly impact their aggregation propensity.

Oxidation is a prevalent degradation pathway, with potential effects on the immunogenicity and biological activity of recombinant proteins, drawing particular attention in quality control. Methionine and cysteine are amino acids prone to oxidation. During the production of recombinant protein pharmaceuticals, methionine is susceptible to oxidation when transitioning from serum-containing to serum-free media, leading to methionine sulfoxide or even methionine sulfone derivatives.

Deamidation is commonly encountered during the long-term storage of recombinant proteins and involves amino acids such as asparagine and glutamine. Asparagine deamidation proceeds through the formation of a succinimide intermediate, which subsequently hydrolyzes into aspartic acid or isoaspartic acid; the latter, being a non-natural amino acid, possesses potential immunogenicity. Deamidation rates are influenced by several factors, including protein structure, solution properties, specific amino acid sequences, secondary structure, pH, and temperature.

Glycation, distinct from glycosylation, represents another common modification that occurs without the involvement of enzymes, primarily as proteins react with reducing sugars. For instance, the aldehyde group of glucose can react with free amino groups in proteins to form a Schiff base, which undergoes Amadori rearrangement to produce glucosamine adducts, marking the Maillard reaction. These chemical modifications alter protein conformation and colloidal stability, thereby affecting aggregation tendencies.

3. Temperature

Temperature plays an essential role in the process of protein aggregation. Elevated temperatures accelerate chemical reaction rates, with reactions such as oxidation and deamidation becoming more prevalent or pronounced in high-temperature environments. Additionally, increased temperature enhances the thermal motion of protein molecules, significantly raising the frequency and velocity of inter-molecular interactions, thereby increasing the likelihood of aggregation. When temperatures surpass a threshold, the higher-order structure of proteins is disrupted, leading to denaturation and exposing previously hidden hydrophobic groups, further promoting aggregation.

4. Solution Environment

Protein stability is intricately linked to its solution environment, with pH being a critical factor. The pH level can affect both conformational and colloidal stability. When the solution pH is at a protein's isoelectric point (IP), solubility decreases, increasing the potential for precipitation and aggregation. Furthermore, pH influences the rate and direction of chemical degradation processes, such as deamidation, where variations in pH conditions alter reaction rates and products. Shifts in solution pH can modify interactions between native protein structures, impacting aggregation dynamics.

Ionic strength also affects the extent of protein aggregation by modulating the conformational stability and protein-protein interaction characteristics. Generally, the impact of ionic strength is contingent on the solution's pH level. Cationic and anionic salts interact with protein molecules, adjusting aggregation through specific or non-specific mechanisms, such as divalent metal ions promoting precipitation and aggregation.

Incorporating excipients is a common strategy to regulate protein aggregation. Substances like arginine, sucrose, and surfactants can reduce aggregate formation under certain conditions. However, some stabilizing agents might inadvertently enhance aggregation under specific circumstances. For instance, sucrose or trehalose can promote aggregation during agitation, while surfactants like polysorbate, despite reducing aggregation during shaking or freeze-thaw cycles, may contain impurities contributing to aggregation.

5. Protein Concentration

Protein concentration has a direct effect on aggregation. Proteins in solution continuously exhibit Brownian motion, with increased concentration amplifying this effect, leading to a higher number of molecules per unit volume. This increase in Brownian motion heightens inter-molecular interaction opportunities and enhances collision probabilities, significantly increasing the likelihood of aggregate formation. Consequently, controlling protein concentration is a vital aspect of managing aggregates during the development and production of protein-based therapeutics.

6. Other Influences on Protein Aggregation

Beyond these factors, multiple other elements can induce protein aggregation. Freeze-thaw processes, for instance, can cause denaturation and instability, with ice formation prompting protein adsorption or denaturation. Processes like centrifugation, filtration, stirring, and pumping introduce mechanical forces that generate gas-liquid interfaces, leading to adsorption, unfolding, and aggregation. Shear stress and exposed hydrophobic surfaces further drive aggregation, as observed in stirring and blending processes.

Light exposure also influences proteins by inducing photolytic and non-photolytic products that enhance aggregation tendencies. Research indicates that antibody solutions exposed to ultraviolet or visible light can form high-molecular-weight aggregates.

Fermentation conditions, including media composition, cell density, and induction temperature, impact protein folding and modifications, subsequently promoting aggregation, as seen in E. coli fermentation resulting in inclusion bodies.

The purification process may induce aggregation with factors such as elution buffer pH, salt concentration, and chromatographic techniques influencing stability. For example, acidic conditions during Protein A affinity chromatography can compromise protein stability, while hydrophobic chromatography packing materials foster strong interactions that might lead to aggregation.

Drying procedures, by removing hydration layers, can lead to aggregation, with proteins often aggregating during freeze-drying or spray-drying processes. Factors in manufacturing and storage of protein-based pharmaceuticals demand careful attention to effectively control aggregation.

You may interested in

Learn More

Impact of Cell Culture Parameters on Protein Aggregates

1. Cell Culture Temperature

Temperature is a critical parameter in cell culture processes, significantly impacting the levels of protein aggregates. Lowering the culture temperature has been observed to increase aggregate formation. This is attributed to enhanced stability of messenger RNA (mRNA) for light chain (LC) and heavy chain (HC) at reduced temperatures, which promotes expression of both chains. However, lower temperatures can limit the processing capacity of the endoplasmic reticulum, hindering proper protein folding and assembly within cells. Consequently, misfolded or incomplete proteins tend to accumulate, leading to increased aggregation. Thus, cell culture temperature emerges as a vital factor influencing the formation of protein aggregates.

2. Stirring Speed

Stirring speed plays a significant role in the formation of protein aggregates, with higher speeds promoting aggregate levels. Increased stirring speeds generate substantial shear forces, which can adversely affect post-translational modifications of proteins, disrupting normal processing pathways. This disruption may lead to errors in protein folding and assembly, resulting in a higher prevalence of misfolded or partially assembled proteins. These defective proteins are prone to interact and aggregate, thereby elevating aggregate levels. As such, stirring speed is a crucial factor that must be carefully managed to mitigate the formation of protein aggregates.

3. Antifoaming Agents

The addition of antifoaming agents during cell culture exerts a crucial influence on protein aggregate levels by reducing their formation. Foaming and associated stirring introduce shear forces that can negatively impact cells, interfering with protein post-translational modifications and leading to aggregate formation. Antifoaming agents effectively mitigate the adverse effects of shear forces caused by foam and agitation, creating favorable conditions for protein modifications to proceed unimpeded. This adjustment fosters proper protein processing, diminishing the likelihood of aggregation due to aberrant protein modifications and consequently lowering aggregate levels.

4. Osmolarity

Maintaining suitable osmolarity can contribute to the reduction of protein aggregates. Changes in osmolarity influence the hydration layer surrounding protein molecules and the intermolecular forces at play. An optimal osmotic environment helps sustain protein stability, reducing the propensity for aggregation due to intermolecular interactions. Furthermore, there exists an interplay between pH and osmolarity; optimal conditions for both can synergistically lower aggregate levels. This interaction is likely explained by a mutual reinforcement in maintaining the stability of protein solutions, optimizing the protein's environment, and thereby suppressing aggregate formation.

References

- Mahler HC, Friess W, Grauschopf U, Kiese S. Protein aggregation: Pathways, induction factors and analysis. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2009;98(9):2909-2934. DOI: 10.1002/jps.21566

- Roberts CJ. Therapeutic protein aggregation: mechanisms, design, and control. Trends Biotechnol. 2014 Jul;32(7):372-80. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.05.005. Epub 2014 Jun 4. PMID: 24908382; PMCID: PMC4146573.

- Wang W, Nema S, Teagarden D. Protein aggregation--pathways and influencing factors. Int J Pharm. 2010 May 10;390(2):89-99. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.02.025. Epub 2010 Feb 24. PMID: 20188160.